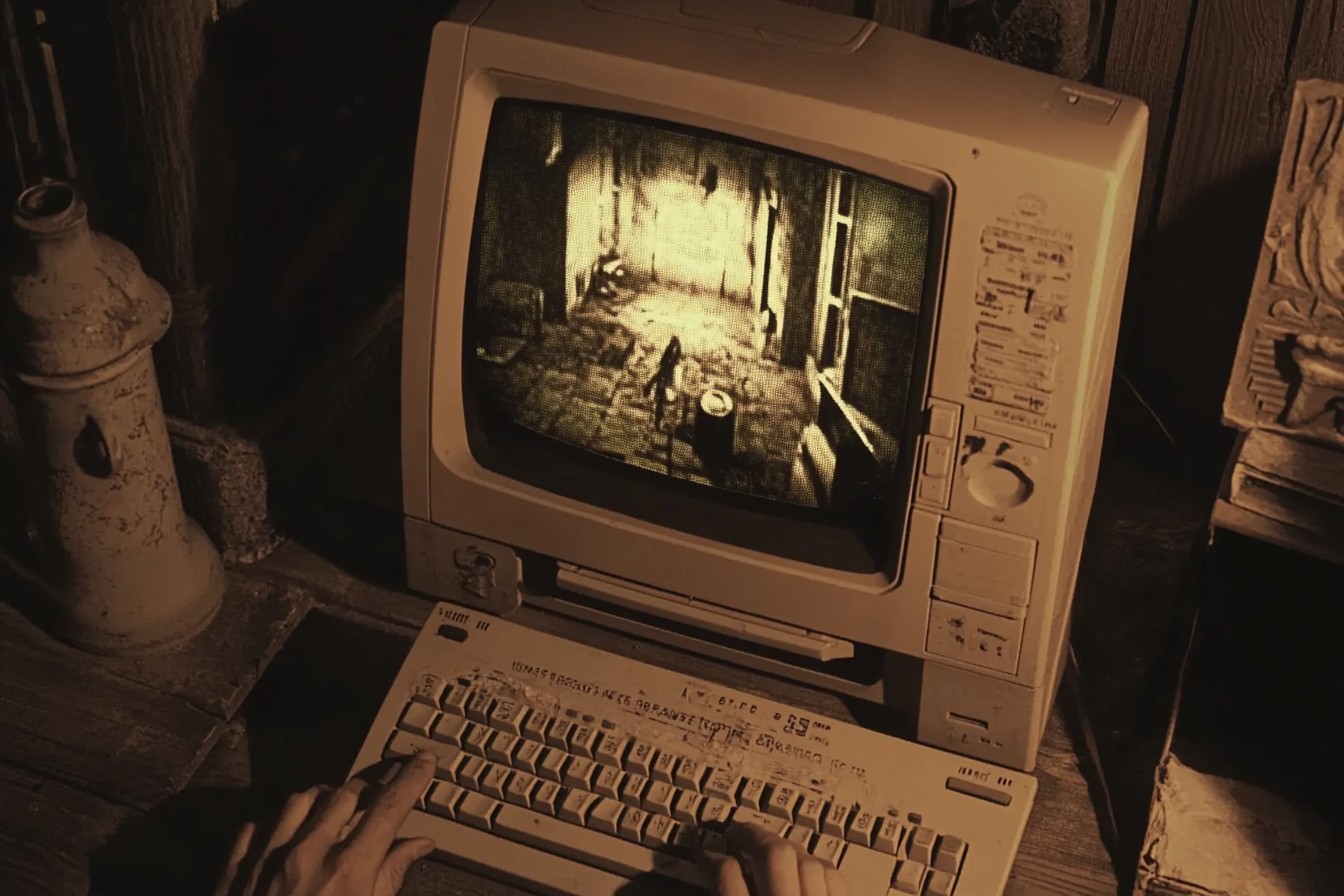

I first played Alone in the Dark on a sticky summer night in 1993, sitting in my friend Kevin’s basement where the family computer had been banished due to his dad’s complaints about the space it took up in the home office. This was back when a PC was a serious investment, a beige monolith with a 486 processor and a whopping 8MB of RAM that his parents had purchased “for school work,” a noble lie that lasted approximately three days before it became a dedicated gaming machine.

Kevin had been talking up this new game for weeks, something “completely different” that would “freak me out.” I was skeptical. I’d played plenty of games that claimed to be scary—Haunted House on Atari, Friday the 13th on NES—but the technological limitations of the time meant “scary” usually translated to “slightly unsettling if you really use your imagination.” But this was 1992, the dawn of CD-ROM gaming, and everything was about to change.

The game began with a choice between two characters: Edward Carnby, a private detective, or Emily Hartwood, the niece of the mansion’s owner. I picked Carnby because he looked slightly more capable in his pixelated form, a decision that Kevin immediately mocked. “The girl actually has a slightly larger inventory,” he informed me, knowledge clearly gleaned from a gaming magazine since the internet wasn’t yet a household fixture. I stuck with my choice out of stubbornness, a personality trait that would both help and hinder me throughout my Alone in the Dark journey.

When the first screen appeared—Carnby standing in the mansion’s attic—I was immediately disoriented. The Alone in the Dark fixed camera angles design was unlike anything I’d experienced. Previous games either used first-person views or side-scrolling perspectives, but here the “camera” was positioned in specific locations throughout the mansion, creating cinematic views of each room. As I moved between areas, the perspective would dramatically shift, creating a disorienting effect that was both frustrating and, I soon realized, brilliant for creating tension. You never knew what might be lurking just off-screen, just beyond what the fixed angle allowed you to see.

The character models were crude by today’s standards—blocky polygons filled with flat colors—but in 1992, the Alone in the Dark polygon character models early implementation was revolutionary. Previous games had used sprites, but these were actual 3D models moving through pre-rendered backgrounds. The effect was uncanny, adding to the unsettling atmosphere. Carnby moved stiffly, a limitation of the technology that would later be spun into a deliberate design choice called “tank controls” in the survival horror genre.

These controls, I soon discovered, were a special kind of torture. The Alone in the Dark tank controls difficulty became instantly apparent as I tried to navigate Carnby through the mansion. Instead of moving in the direction you pushed the joystick, you rotated the character and then moved them forward or backward relative to the way they were facing. Combined with the changing camera angles, this meant constantly readjusting your mental map of which button did what. “Left” could suddenly become “right” after a camera change, sending you running straight back into the danger you were trying to escape.

“This is awful,” I complained after my third failed attempt to simply walk down a hallway without looking like a drunk sailor. Kevin just grinned. “You’ll get used to it. You have to.”

He was right, I did eventually adjust, but the clumsy navigation never became second nature. In retrospect, I realize this was part of the game’s genius. The Alone in the Dark survival horror defining elements included making the player feel vulnerable not just through direct threats, but through mechanical limitations. You were supposed to feel uncomfortable, supposed to struggle. The control scheme wasn’t broken; it was deliberately designed to undermine your mastery, keeping you perpetually on edge.

The inventory system further reinforced this vulnerability. The Alone in the Dark inventory management survival mechanics limited what you could carry, forcing painful decisions about which items to take and which to leave behind. Should I carry an extra oil lamp for dark areas, or another weapon? That ancient book might contain crucial information, but it took up valuable space that could hold healing items. I found myself constantly returning to storage chests, rearranging my limited resources, trying to anticipate what horrors might lie ahead.

The first genuine scare came about fifteen minutes in. I was exploring a room when suddenly the piano in the corner began playing by itself. Before I could react, a purple zombie-like creature crashed through the floor. Kevin, who had been watching silently, burst out laughing at my reaction, which involved a yelp and reflexively throwing the mouse across his desk. “Told you it was scary,” he said, retrieving the mouse while I tried to compose myself.

The combat system was clunky and limited, another deliberate choice that heightened tension. You had a few basic attacks—punches, kicks, and the occasional weapon—but fights never felt empowering. Each encounter was a desperate struggle rather than an opportunity for heroics. Many enemies couldn’t be defeated permanently, only temporarily incapacitated, encouraging avoidance over confrontation. This was survival horror in its purest form—the focus wasn’t on killing monsters but on simply surviving them.

The puzzles formed the backbone of progression, ranging from logical to absolutely maddening. The Alone in the Dark puzzle solution guide existed only in physical form, in gaming magazines or official hint books, with no way to quickly look up answers online. One particularly frustrating sequence involved a library with moving bookshelves that could crush you if you didn’t navigate them in the correct sequence. After dying repeatedly, Kevin finally admitted he’d been stuck there for days before finding the solution in a PC Gamer magazine. I felt slightly vindicated that my struggles weren’t due to incompetence but genuine difficulty.

What elevated Alone in the Dark above a mere technological curiosity was its atmosphere and story. The Alone in the Dark Lovecraft influence story was apparent throughout, drawing heavily from the cosmic horror tradition without directly adapting any specific work. The mansion’s owner, Jeremy Hartwood, had committed suicide after discovering unspeakable secrets. As the game progressed, journal entries and books revealed a history of dark rituals, ancient entities, and a malevolence that permeated the mansion itself. The narrative unfolded organically through exploration rather than exposition dumps, rewarding curiosity while simultaneously making you dread what you might discover.

Knowledge of the Alone in the Dark mansion map layout became crucial not just for navigation but for survival. Certain rooms contained safe havens, others deadly traps. The mansion felt architecturally coherent, each room logically connected to others, creating a space that began to feel familiar even as it remained threatening. I started to create a mental map, plotting safe routes between areas and noting which rooms contained useful items or dangerous enemies. This spatial awareness became as important as any inventory item.

We played through most of the night, trading the keyboard and mouse whenever one of us died or got stuck. By around 3 AM, Kevin’s parents had long since gone to bed, and the basement’s small windows showed nothing but darkness outside. The only light came from the computer monitor, casting everything in an eerie glow that perfectly matched the game’s atmosphere. At one point, the house’s heating system kicked on with a groan that sounded disturbingly like one of the game’s monsters, causing both of us to freeze momentarily. We looked at each other and burst into nervous laughter.

“Maybe we should continue tomorrow,” Kevin suggested, clearly as unsettled as I was. I agreed too quickly, trying not to seem as eager to stop as I actually felt. The game had succeeded in creating an atmosphere that followed us beyond the screen, turning Kevin’s familiar basement into something slightly sinister. That, I realized later, was perhaps Alone in the Dark’s greatest achievement—it made you carry its dread with you even after you stopped playing.

In the years that followed, I watched as the Alone in the Dark versus Resident Evil comparison became a common topic among gaming enthusiasts. Resident Evil, released four years later in 1996, clearly built upon the foundation that Alone in the Dark established, from the fixed camera angles to the limited inventory and emphasis on atmosphere over action. But Resident Evil had the advantage of improved technology and a larger budget, allowing for pre-rendered backgrounds with more detail and FMV cutscenes that enhanced the storytelling. It refined the formula rather than invented it, streamlining some of the more frustrating elements while maintaining the core tension.

I eventually returned to Kevin’s house to finish the game over several more sessions. The final confrontation took place in the mansion’s caves beneath the basement, a labyrinthine network where the game’s Lovecraftian themes reached their zenith. The final enemy, a tree monster called “the tree guardian,” required specific items and actions to defeat. There was no epic battle, no triumphant victory—just a desperate scramble to complete a ritual before being overwhelmed. When we finally succeeded, the payoff was a brief cutscene showing the mansion exploding as Carnby walked away. It felt anticlimactic at first, until we realized it perfectly matched the game’s tone. You didn’t win; you merely survived.

Looking back, I can see how Alone in the Dark shaped not just the survival horror genre but my own relationship with games. It was the first time I experienced a game that wasn’t focused on empowerment or achievement but on creating a specific emotional state—in this case, vulnerability and dread. It showed me that games could be more than tests of reflexes or puzzle-solving; they could be experiences that lingered in your mind, that affected how you felt.

I revisited the game decades later through an abandonware site, curious if it would hold up or if my memories had enhanced its impact. The graphics, of course, looked primitive compared to modern standards. The polygonal characters resembled origami figures more than people, and the pre-rendered backgrounds that once seemed realistic now looked flat and artificial. But surprisingly, the core experience remained effective. The fixed cameras still created moments of tension as I moved between angles. The limited inventory still forced meaningful choices. And the atmosphere, enhanced by the excellent sound design of creaking floorboards and distant moans, still created a sense of dread.

What struck me most was how the game’s limitations, both technological and deliberate, contributed to its effectiveness. Modern horror games have vastly more sophisticated tools—realistic graphics, dynamic lighting, advanced AI—yet many fail to create the same sense of vulnerability and tension that Alone in the Dark achieved with its blocky polygons and pre-rendered rooms. There’s a purity to its approach, an understanding that true horror comes not from what you can see but what you can’t, not from what you can do but what you’re prevented from doing.

The modern survival horror genre has evolved significantly since 1992, with titles like Amnesia, Outlast, and Alien: Isolation pushing the boundaries of what interactive horror can achieve. Yet they all owe a debt to that pioneering title that dared to make players feel helpless rather than powerful, that understood restriction could be more compelling than freedom. When I play these modern games, I sometimes think back to that summer night in Kevin’s basement, to that first moment when a polygonal monster crashed through the floor and I realized games could genuinely frighten me.

Alone in the Dark wasn’t just a game that pioneered survival horror; it was a game that changed how I understood the medium’s potential. It showed that games could create emotional states beyond fun or satisfaction, that they could be experiences designed to unsettle and disturb. As I’ve watched the medium evolve over decades, I’ve seen this understanding blossom into games that explore the full spectrum of human emotion, from joy to grief, wonder to horror. And it all started in a virtual mansion where the camera angles were fixed, the inventory was limited, and you were truly, terrifyingly, alone in the dark.