There’s something uniquely satisfying about championing the underdog. Maybe that’s why, nestled between my PlayStation 5 and Switch in my entertainment center, my Sega Saturn still occupies prime real estate. It’s not there for show—I fired it up just last weekend to play through Guardian Heroes again. My girlfriend walked in, saw the chunky polygons and sprite-based characters on our 4K TV, and asked with genuine confusion, “Is this what you’re choosing to play when you have literally every modern game at your fingertips?” Yes. Yes it is. I came to the Saturn in what you might call unusual circumstances. It was 1996, and I’d been saving for months to buy a PlayStation. Sony’s grey miracle machine was the hot ticket—everyone at school talked about Resident Evil and Tomb Raider with religious reverence. But fate had other plans. My uncle Ted, who worked at an electronics store, called with news that would alter my gaming trajectory: they were clearing out their Saturn inventory at fire sale prices. “I can get you the console and five games for less than the PlayStation by itself,” he said. To a 16-year-old with limited funds, that math was irresistible.

The day I brought that black angular box home, I had no idea I was joining what would essentially become a cult. The Saturn had already been labeled a failure by gaming magazines, its complex architecture and surprise early launch consequences putting it firmly behind Sony’s upstart console. But I didn’t care about market share or corporate strategy—I cared about games, and my Saturn came bundled with Virtua Fighter 2, Daytona USA, and NiGHTS Into Dreams. That first weekend disappeared in a blur of fighting game combos, drifting race cars, and flying through psychedelic dreamscapes. The Sega Saturn surprise early launch is legendary in gaming circles now—the industry’s most notorious self-sabotage. At E3 1995, Sega announced the Saturn was available immediately, four months ahead of schedule, at select retailers for $399. It sounds bold until you realize developers weren’t ready, retailers who weren’t chosen were furious, and most importantly, Sony immediately countered by announcing the PlayStation would launch at $299. I still have the EGM magazine with the coverage, the shocked headlines and quotes from blindsided game publishers. Reading it now feels like an autopsy report for Sega’s console dominance. What’s tragic is that beneath the business blunders lay hardware with remarkable capabilities.

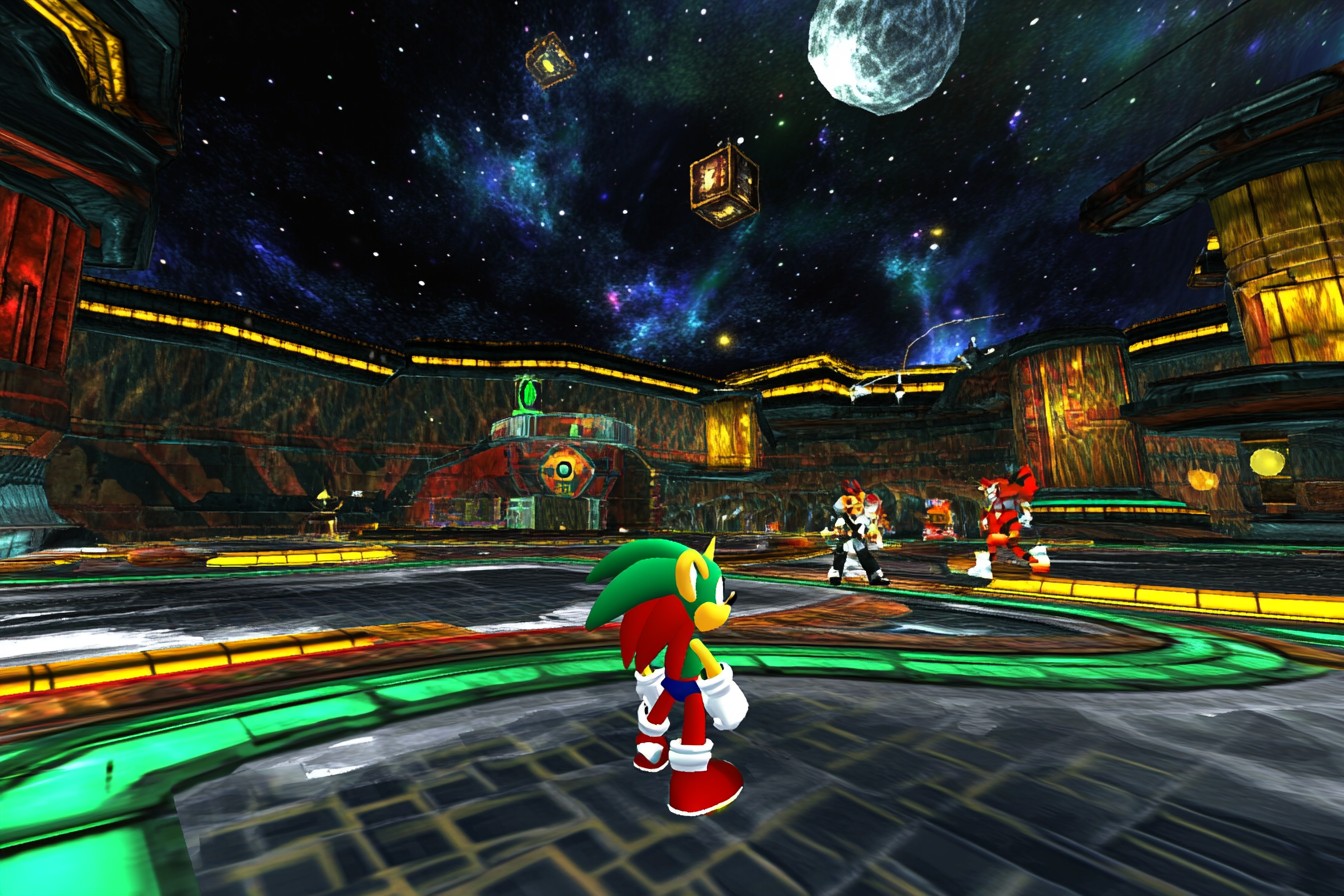

The Sega Saturn vs PlayStation hardware comparison wasn’t as straightforward as the “PlayStation is better” narrative suggested. Yes, the PlayStation excelled at 3D, with dedicated hardware that made polygonal graphics more straightforward to implement. But the Saturn’s dual Hitachi SH-2 processors and additional sound and video chips made it a powerhouse for 2D games and complex sprite manipulation. It was like Sega had built a formula one car but gave developers a manual written in ancient Sumerian—the power was there, but harnessing it required expertise few possessed. The Sega Saturn 2D sprite capabilities remained unmatched during that era. Games like Guardian Heroes and Marvel Super Heroes showcased what the system could do with traditional 2D graphics—fluid animation, massiv

e sprites, and minimal slowdown even with dozens of characters on screen. While the PlayStation was pushing early 3D with all its jagged edges and texture warping, the Saturn was delivering arcade-perfect 2D experiences. It was like having a Neo Geo-level sprite performer hiding in your living room. The fighting game scene on Saturn was where I found my people. The Sega Saturn Virtua Fighter arcade perfect port became my obsession. I’d previously played the game in arcades, dropping quarters with reckless abandon, but having it at home changed everything. I could practice Akira’s moves for hours, perfecting timing without financial penalty. My friend Marcus and I developed a Friday night tradition—pizza, Mountain Dew, and Virtua Fighter tournaments until dawn. We created brackets, tracked statistics, and took the whole thing way too seriously.

My parents thought we were insane, but they didn’t understand the importance of mastering Wolf’s pile driver. The real treasure trove, I discovered later, was Sega Saturn Japanese exclusive games. I stumbled across this revelation thanks to Dave, whose older brother was stationed in Okinawa. Dave’s brother would send back these exotic Saturn titles with incomprehensible Japanese text but instantly playable gameplay. Radiant Silvergun, Sakura Wars, Dragon Force—games that never made the journey westward but showcased what the system could really do. I bought a cartridge that bypassed the region protection, transforming my American Saturn into a portal to Japanese gaming culture.

My parents questioned why I was spending $80 on import games I couldn’t read. “The gameplay transcends language,” I explained, which satisfied no one but myself. Collecting for the Saturn has become both a passion and a financial black hole. Sega Saturn collecting rare games is not for the faint of heart or light of wallet. The system’s commercial failure meant many great games had limited production runs, creating a perfect storm for future collectibility. I found my copy of Panzer Dragoon Saga at a flea market in 1999 for $15, the seller clearly unaware he was practically giving away what would become one of the most valuable games in collecting circles. Today it’s worth north of $1,000 complete, though I’d sooner sell a kidney than part with it. The 30-hour adventure through that weird, beautiful post-apocalyptic world remains one of my defining gaming experiences. The physical quirks of the system added to its character.

Those Sega Saturn disc protection rings—the clear plastic pieces in the center of the disc—were supposedly designed to strengthen the CDs but seemed purpose-built to crack under normal use. I became adept at detecting hairline fractures before they catastrophically failed, replacing favorite games before they became unplayable. I had three copies of NiGHTS over the years, each replacement more expensive than the last as the game became harder to find. The Saturn’s equipment quirks extended to the controllers, too. That original controller was a monstrosity—overdesigned with an awkward shape and mushy D-pad. The later Japanese model 2 controller fixed these issues, becoming one of the best controllers of that generation, but the damage to the console’s reputation was already done. Speaking of

NiGHTS, Sega Saturn NiGHTS into Dreams Yuji Naka creation deserves special recognition. This wasn’t just a game; it was a flying dream simulator that defied categorization. Naka, fresh off Sonic Team’s success, created something utterly unique—a game about a jester flying through dream worlds, collecting orbs and linking combos through giant hoops. The concept sounds absurd explained aloud, but playing it created a flow state unlike anything else at the time. The Christmas NiGHTS demo disc that came bundled with gaming magazines might be the most played Saturn disc in my collection—a seasonal tradition I maintain to this day, much to the confusion of holiday guests. Among collectors and enthusiasts, conversations inevitably turn to Sega Saturn hidden gems worth playing.

Beyond the obvious choices like Panzer Dragoon and NiGHTS, I’ve evangelized for overlooked titles like Burning Rangers (a firefighting game by Sonic Team), Shining Force III (only one of three connected chapters made it westward), and Enemy Zero (a first-person horror game with invisible enemies tracked only by sound). These games showcased developers who understood the hardware, wringing impressive performance from the complicated architecture. They weren’t just good Saturn games—they were good games, period, that suffered from being on the wrong platform at the wrong time. The Saturn’s fortunes varied dramatically by region. While it struggled in North America, in Japan, the console was initially successful, battling neck-and-neck with the PlayStation for years. The Japanese market’s preference for 2D titles like fighting games and RPGs aligned perfectly with the Saturn’s strengths. My collection of imported Japanese Saturn magazines (another collecting rabbit hole I fell into) shows a vibrant ecosystem of games and peripherals that never made it to Western shores. One magazine featured a house where every electronic device connected to a Saturn—TV tuners, home security, even kitchen appliances. It was Sega’s vision of a connected future with the Saturn at its heart—a future that never materialized outside Japan.

Technical limitations created their own charm. The Saturn struggled with transparency effects—developers had to use mesh patterns instead of true transparency, giving games a distinctive dithered look. What was originally a limitation became an aesthetic, one I’ve grown nostalgic for. The fog in Panzer Dragoon wasn’t just atmospheric; it was hiding the limited draw distance. These technical workarounds created unique visual identities that distinguished Saturn games from their PlayStation counterparts. My Saturn collection now spans over 150 games, a mix of American, European, and Japanese releases housed in those fragile long boxes and jewel cases.

Each has a story—the copy of Shining Wisdom I traded my entire Magic: The Gathering collection for; the Dragon Force disc I rescued from a water-damaged basement; the Magic Knight Rayearth I finally found complete after a decade of searching. My modest apartment has bookshelves dedicated solely to Saturn games, arranged by publisher rather than alphabetically (a system my girlfriend finds maddening but I insist has an internal logic). Every few years, mainstream gaming media rediscovers the Saturn, pub

lishing “Was the Saturn Actually Good?” retrospectives that make long-time fans both validated and irritated. Yes, it was actually good—we’ve been saying this for 25 years! The console is finally getting its due, recognized for its ambition and library rather than its market performance. It’s like watching a critically panned movie become recognized as a masterpiece decades later, except I get to be insufferably smug about being right all along. The legacy of the Saturn lives on through emulation and the collectors’ market, but nothing compares to the authentic experience—that distinctive startup sound, the slight loading hiccup between disc accesses, the peculiar smell of the plastic casing that somehow differs from other consoles of the era.

Modern convenience has eliminated these sensory aspects of retro gaming, the little frictions that were part of the experience. Last winter, during a power outage, I pulled out a battery-powered CRT TV I keep for retro gaming emergencies (yes, that’s a thing I have, and no, I don’t have an emergency fund, why do you ask?). In the quiet darkness of the blackout, the Saturn’s startup sequence illuminated the room with its iconic blue, green, and red spheres merging into the Sega logo. My girlfriend, previously bewildered by my attachment to this outdated technology, sat down beside me for a session of Bomberman. Four hours later, when the power returned, she looked almost disappointed. “I get it now,” she admitted. And that’s the thing about the Saturn—it was never about polygon counts or market share. It was about games that tried something different, developers pushing against technical limitations to create memorable experiences. My PlayStation friends were playing the same blockbuster titles everyone else was, while Saturn owners were discovering weird gems like Elevator Action Returns or Three Dirty Dwarves.

Being a Saturn fan meant being part of a dwindling tribe, exchanging knowing nods when spotting someone reading a Saturn magazine at the mall, or the hushed excitement of finding a Saturn game in the wild. It wasn’t just a console; it was membership in a community united by championing something brilliant but misunderstood. Maybe that’s why, decades later, as gaming has become mainstream and franchises have calcified into predictable annual releases, I still return to my Saturn. Not just for nostalgia, but for that feeling of discovery, of playing something that dared to be different, created by developers who had to be clever to overcome technical hurdles. In an era of gaming defined by excessive tutorials and hand-holding, there’s something refreshing about the Saturn’s catalogue—games that respect the player’s intelligence and reward experimentation. So yes, my Saturn stays in the entertainment center, not as a conversation piece or collector’s showpiece, but as a still-active portal to gaming’s most fascinating failed timeline—the path not taken, where Sega remained a hardware leader and the industry zigged instead of zagged. Every time that startup sequence plays, I’m reconnecting with not just my personal gaming history, but an alternate universe of gaming that exists now only in the collections and memories of those who recognized the underrated gem the Saturn truly was.